The food supply of the Secret Annex

Anne Frank's diaries provide a lot of information about what was eaten in the Secret Annex. What was available depended heavily on supply and opportunities to get around rationing restrictions and other problems.

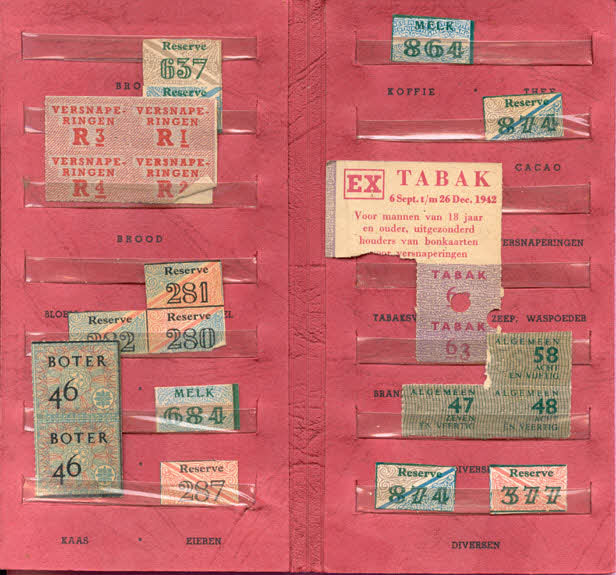

Bonnenboekje

Collectie: Anne Frank Stichting Copyright: AFS rechthebbende

The theme of food is closely related to the topics of Rationing and Supply in general. After all, what was eaten, and how much, partly depended on these aspects. Food was not initially lacking in the Secret Annex. Sufficient food was available through regular and clandestine distribution channels.

From 8 August 1943, a 'customer loyalty' scheme for fruit and vegetables came into effect in many places, including Amsterdam. This meant that every household had to commit to a regular greengrocer for each four-week period. The latter issued a 'family card' by name and had to ensure collection of vouchers and reasonable distribution of his supply, depending on the number of family members.[1] How the helpers solved this complication in practice is not known.

Vegetables and potatoes came from greengrocer Van Hoeve on Leliegracht; for bread, an arrangement was made with baker Siemons.[2] Meat came from a butcher in the area known to Hermann van Pels, probably - based on the menu mentioned below with 'Roastbeaf SCHOLTE' - Piet Scholte's branch on Elandsgracht.[3] As time passed, difficulties arose, which had several causes. Victor Kugler wrote years later in his recollections that gradually the problems grew; food in particular became scarce.[4] Austerity of meals and rations repeatedly gave rise to quarrels. Using Anne's notes and various external sources, various aspects of the issue can be well described and also explained.

Diet and its shifts

At the start of the hiding period, a substantial stock of food had been established, including one hundred and fifty tins of canned vegetables. Through business contacts, powdered milk, wheat starch and sugar were always available in ample quantities, with which, according to Kugler, nutritious puddings could be made.[5]

In the late summer and autumn of 1942, Anne writes that she and Hermann van Pels ate heavily.[6] At the same time, fat rations steadily decreased in the second half of 1942.[7] On 7 October that year, we can read about the tensions caused by whether or not butter was spread on bread in the Secret Annex.[8] At the time, the official butter/fat ration amounted to 62½ grams per person per week.[9] Anne reports the delivery of 135 kilos of pulses in November.[10] In March 1943, she writes that her mother arranged for the children to receive extra butter.[11] However, it was the rationing system that determined that the youth between the ages of 4 and 21 received a higher fat ration.[12] On the same day, she writes that she got tired of white and brown beans, and that the 'evening bread ration' had been withdrawn.[11] The abundance of beans can be explained by the aforementioned 135 kilos. Given the lenient arrangement with Siemons, why bread consumption was reduced is unclear.

It became especially apparent in the first months of 1944 that external factors had a major influence. The arrest of voucher suppliers Brouwer and Daatzelaar in March jeopardised the supply of potatoes and butter, among other things.[13] Fried potatoes for breakfast were therefore replaced by porridge.[14] It proved possible to buy extra whole milk, which was done at Mrs Van Pels' insistence. Whole milk was officially reserved for children under 14, so that purchase was clandestine. Black market milk prices in early 1944 were around 40 to 50 cents per litre in Amsterdam-Noord and up to 1.30 to 1.50 guilders per litre in Zuid.[15] So it's likely the people in hiding incurred relatively high costs for extra milk. This suggests that shortages in the Secret Annex were due more to scarcity and distribution problems than to lack of money.

Anne complained on 8 May 1944 that they were constantly eating 'lettuce, stewing lettuce, spinach, spinach and more spinach '. During this period, a shortage of fertilisers led to crop restrictions. Especially the 'mass products' were widely available then, a category that included the controversial leafy vegetables.[16]

Problems did grow after the arrest of greengrocer Van Hoeve in late May 1944. The growing shortage of potatoes and vegetables led to the gradual abolition of breakfast.[17] Compensating by bringing lunch forward could not conceal the fact that scarcity had increased.

Extras

There was room to do something extra now and then. In the early days, the Franks, at that time alone in the Secret Annex, received rhubarb, strawberries and cherries from the helpers.[18] To mark Jan and Miep's wedding anniversary, there was a dinner in the Secret Annex on 18 July 1942, just after the Van Pels family arrived. A typed menu of this has been preserved, and on the table were broth, roast beef, various salads and one 'pomme de terre' per person. Also gravy, 'to be used very minimally' because of the butter ration, riz à la Trautmannsdorf ('surrogate') and coffee with sugar and cream.[3] Bouillon and gravy powders were part of Gies & Co's core range. Given the prevailing scarcity and therefore very high prices, the coffee must also have been 'surrogate'. When Jan and Miep came to stay in October, soup, meatballs, potatoes, carrots and coffee with gingerbread and Maria biscuits were served, according to Anne.[19]

Through the story Sausage Day and from the B-version, the episode situated by Anne in December 1942 is known in which Van Pels had managed to get hold of a large quantity of meat and made sausage from it.[20] Through food distribution, the people in hiding sometimes benefited from occasional windfalls, as in the provision of extra sweets, oil and syrup at Christmas.[21] On the other hand, they also noticed when a butter coupon was withheld as a sanction for the 1943 strikes. From the same note comes the list of foodstuffs apparently sent to Pfeffer by Charlotte Kaletta on his birthday in 1943: eggs, butter, biscuits, lemonade, bread, brandy, oranges, gingerbread and chocolate.[22]

In late 1943, the helpers managed to get 'pre-war' butter biscuits for the people in the Secret Annex, and on Edith's birthday a few weeks later, a 'pre-war' mocha cake.[23] On Otto Frank's 55th birthday there was beer, and through Siemons there were even fifty 'pre-war' petit fours.[24] In the case of the cake and pie, this meant that the relevant bakers must have been provided with necessary ingredients such as butter, sugar and eggs in advance via the helpers. As bakers were sparsely supplied with these, this was a common method of obtaining decent - 'pre-war' - pastries at the time.[25]

In July 1944, Mrs Van Hoeve - her husband was imprisoned at that time for hiding the Jewish couple Weisz - delivered nine kilos of peas. The pods of these were also eaten. On the same day, Anne notes the delivery of a large batch of strawberries, taken by Broks directly from the Beverwijk auction.[26] Given the quantities, these must also have been non-regular transactions. Clandestine trade in strawberries was also closely monitored in Amsterdam around this time.[27]

Finally, there was Peter's cat Mouschi. After much deliberation and ambiguity, the government decided that food could only be available for economically useful cats, such as warehouse cats.[28] This meant that Mouschi's food, unlike that of warehouse cat Moffie, had to come through other channels, or he ate what the people in hiding ate.

This overview shows that external factors played a greater role in the impoverishment of the food position in the Secret Annex than internal ones. The decline in variety and quantities kept pace with the disappearance of suppliers of coupons and foodstuffs. Financial concerns undoubtedly made themselves felt, yet repeatedly it appears that occasional opportunities to purchase extras remained for a long time. Lack of money therefore does not seem to have been a decisive factor in the decline of the food position.

Footnotes

- ^ “Klantenbinding voor groente en fruit”, De Tijd, 24 juli 1943.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 5 November 1942, in: The Collected Works, transl. from the Dutch by Susan Massotty, London [etc.]: Bloomsbury Continuum, 2019.

- a, b Anne Frank Stichting (AFS), Anne Frank Collectie (AFC), reg. code A_Gies_I_032: Menukaartje.

- ^ AFS, AFC, reg. code A_Kugler_I_048: Getypte herinneringen Victor Kugler.

- ^ Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach, Archief Ernst Schnabel; Victor Kugler aan Ernst Schnabel, 17 september 1957.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 30 September and 6 October 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Rantsoeneering van levensmiddelen in de bezettingsjaren, [S.l.] : Ministerie van Landbouw, Visscherij en Voedselvoorziening, Afdeeling Voorlichting, [ca. 1945], p. 4-5.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 7 October 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ “Boter op bon 51”, Het Vaderland, 6 oktober 1942, ochtendeditie.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 5 November 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- a, b Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 12 March 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ “Distributie”, De Tijd, 10 maart 1943.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 10 March 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 14 March 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ “Rond de rundveeprijzen”, Provinciale Noordhollandsche Courant, 25 januari 1944.

- ^ “Groente wordt verdeeld in massaproduct en keuze-artikel”, Gooi- en Eemlander, 29 april 1944.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 25 May 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 8 July 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 10 October 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Tales and events from the Secret Annex, “Sausage Day”, 10 December 1942; Diary Version B, 10 December 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 22 December 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 1 May 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 27 December 1943 and 19 January 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 9 and 13 May 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ “Gebak en koek met ‘bijlevering’”, Het Nieuws van den Dag, 4 november 1943.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 8 July 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ “C.C.D. waakte over de aardbeien”, Nieuws van den Dag, 6 juli 1944; “Ruim 2000 pond aardbeien achterhaald”, Provinciale Overijsselsche en Zwolsche Courant, 3 juli 1944.

- ^ Paul Arnoldussen, 'Poes in verdrukking en verzet 1940 – 1945', in: Poezenkrant, (2013) nr. 57, p. 27-30.

Locations (3)

-

The Secret Annex | Prinsengracht 263

Amsterdam

The Secret Annex at Prinsengracht 263, Amsterdam, was the hiding place of Anne Frank with her parents and sister Margot, Hermann and Auguste van Pels with their son Peter, and Fritz Pfeffer. Location

-

Greengrocer's Henk van Hoeve

Amsterdam

Greengrocer Henk van Hoeve helped Miep Gies to supply potatoes to the people in hiding in the Secret Annex during the German occupation. Location

-

Zwolle police station

Zwolle

In March 1944, 'coupon men' Brouwer and Daatzelaar were detained at the Zwolle police station for approximately two weeks. Location