Distribution: food rationing

The government wanted to ensure a good food supply through rationing. But the German occupier was keen to exclude anyone who went into hiding from food supplies.

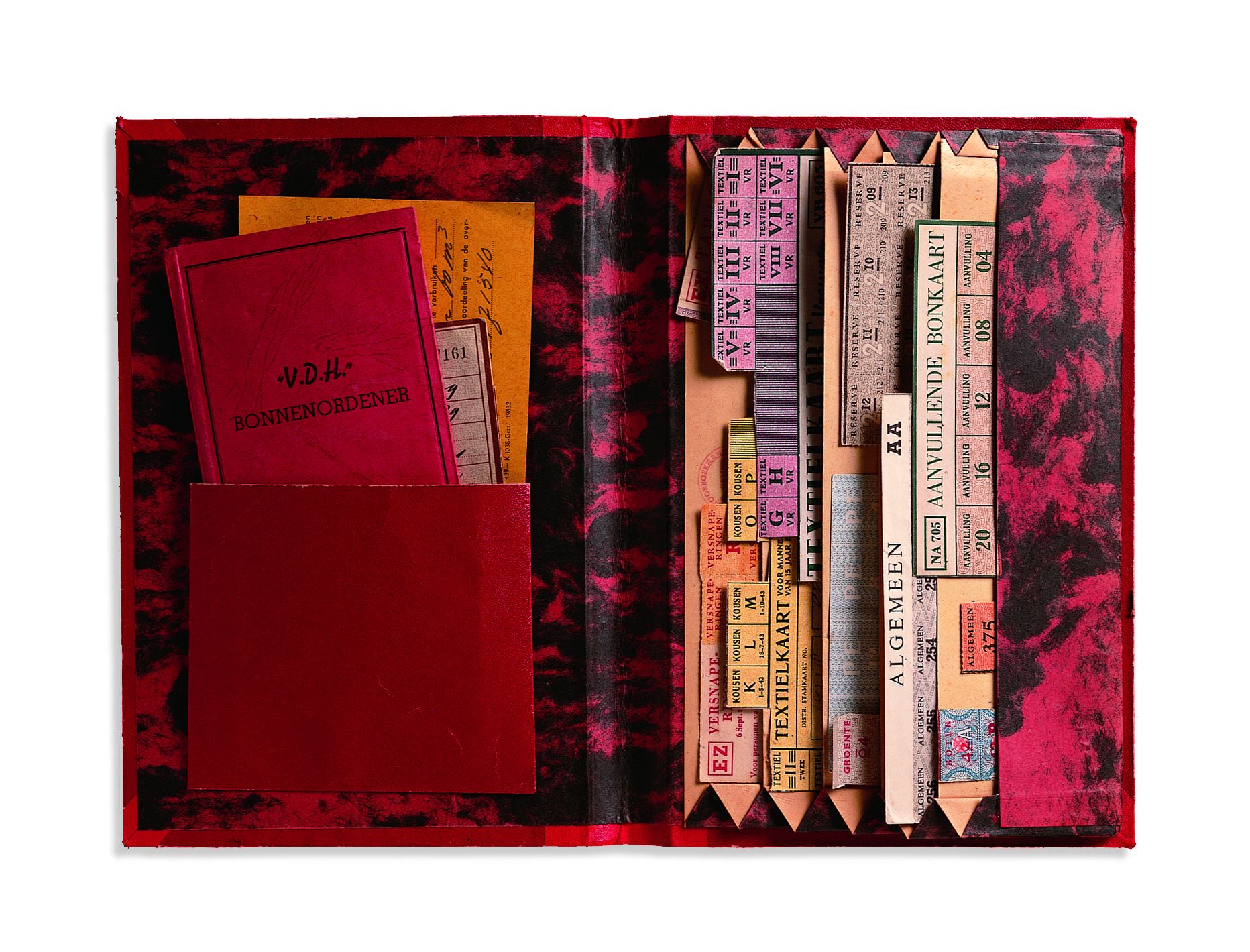

Distributiebonnen

Fotograaf: Allard Bovenberg. Collectie: Anne Frank Stichting. Copyright: AFS rechthebbende

During World War I, food shortages also developed in the neutral Netherlands. When the threat of war increased during the 1930s, the government wanted to guarantee a good food supply through rationing. Rationing was differentiated by age group, with the importance of growing children being especially prioritised. Implementation was done by the municipalities. Allocation took place via the rationing master card (DSK) issued to residents by the municipality. Those in possession of this card were given the opportunity to buy certain goods by means of ration stamps.[1]

On 12 October 1939, sugar went on sale on a trial basis; peas followed on 5 November. There was no shortage at that time.[2] The number of products rationed and the size of the quota changed regularly.[3]

There was a large population of people in hiding during the occupation. Apart from Jews, these were mainly forced labourers who did not return after leave and soldiers who wanted to avoid becoming prisoners of war. In most cases, others were able to collect stamps in their locality without any problems. However, if they were deregistered from the Population Register, their rationing card was put on a 'block list', and the official had to confiscate the master card.[4]

The Van Pels family was deleted from the Population Register at the end of 1942, so their cards were put on the block list. In the case of the Frank and Fritz Pfeffer family, for unknown reasons, this did not happen until late 1944. Presumably, therefore, unlike the Van Pelses, they kept their rationing documents. Anne writes in her diary on 14 March 1944 that the people in hiding had five rationing cards.[5]

On 22 December 1943, Anne writes that they all received extra oil, sweets and a jar of syrup "from rationing".[6] Indeed, at Christmas 1943, a pound of syrup, some sugar and a quantity of extra oil became available to everyone.[7] This meant that the people in the Secret Annex, or at least some of them, were still using the regular rationing system.

In contrast, Anne writes on 5 November 1942 about the switch from 'city' cards to 'countryside' cards.[8] This organisational separation had been in place since 5 September 1942. The 'countryside' cards had the disadvantage that they were not valid for butter, potatoes and milk in urban areas.[9] According to Anne, however, they were a lot cheaper. Moreover, they could sell the bread stamps, as baker Siemons provided 'stamp-free' bread in exchange for lactose. The fact that these stamps were bought shows that the people in hiding and the helpers were also involved in unofficial distribution. Ration stamps were also available through the representatives of Gies & Co. Martinus Brouwer and Hendrikus Daatzelaar.[10] So they got their food partly through regular and partly through clandestinely obtained rationing coupons. The oranges that Charlotte Kaletta sent to Pfeffer were obtained outside the rationing regulations, since these fruits were always reserved for the age group up to 13.[11]

In early 1944, Rauter tried to exclude the tens of thousands of people in hiding from food supplies through a new administrative system. The Second Rationing Master Card (TD) had to be issued according to carefully designed regulations. Every adult had to collect the card in person, bring and sign the summons card, and hand in the old card. A corner of this old card was cut off and stuck on the new one.[12]

In Amsterdam, the civil service, working together, managed to virtually nullify the intended effect. It managed to arrange that in the Beurs (the Stock Exchange) - where the paper work was issued - a hall manager and several under managers were put in place who were 'good'. Officials of the Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages issued thousands of registration cards for Jews who had already been deported but were still registered as residents. These were passed on to people in hiding via the Beurs. The corners to be cut off came from the cards of deceased people or were simply forged. An estimated 20,000 cards thus became available for the benefit of people in hiding.[12] A study published in 1995 showed that the official sabotage had been completely successful:

'In retrospect, it has become clear that Rauter's plan to bring the people in hiding to the surface by introducing the Second Rationing Master Card did indeed fail. Incidentally, the master card could not be put into use until 11 June 1944. By then, Rauter himself knew from the numbers of cards and control stamps issued that the people in hiding had been provided for. His investigation into its causes was not completed due to wartime developments.'[13]

Otto Frank's personal card was number TD174/873029z, which indicated the Second Rationing Master Card. He also used this legally after returning from Auschwitz. Anne had the number TD174/163173 and Margot only TD174. Edith had no rationing papers registered at all, but her card was a post-war '2nd copy.' The original card was lost, possibly due to acts of resistance. Pfeffer had TD174-500778ing. The Van Pels family only had the old DSKs, with the addition 'under investigation.' This meant that officials took advantage of the fact that these five (including probably Edith) were still on the Population Register. Whether those cards actually ended up with them is not certain, but given Jan Gies' illegal contacts it's very possible.

From a public health point of view, the food situation remained adequate until October 1944. For the people in the Secret Annex, however, it was regularly problematic, as they had eight mouths to feed with five cards. Due to the effects of the railway strike, the situation deteriorated rapidly, especially in the cities in the west. The eight people in hiding had been arrested by then.

Even after liberation, trade in various foodstuffs remained restricted for some time. Coffee was the last product freely available again from 14 January 1952, bringing an end to food rationing.[14]

Footnotes

- ^ Nationaal Archief, Den Haag, Centraal Distributiekantoor, 1939-1950, nummer toegang 2.06.037: Inventaris van het archief van het Centraal Distributiekantoor, (1937) 1939-1950 (1955), p. 10 (http://www.gahetna.nl/collectie/archief/pdf/NL-HaNA_2.06.037.ead.pdf).

- ^ G.M.T. Trienekens, Tussen ons volk en de honger. De voedselvoorziening 1940-1945, Utrecht: Matrijs, 1985, p. 41.

- ^ Zie de brochure Rantsoeneering van levensmiddelen in de bezettingsjaren, [S.l.] : Ministerie van Landbouw, Visscherij en Voedselvoorziening, Afdeeling Voorlichting, [ca. 1945].

- ^ Amsterdams Distributiedienst zoals de Duitschers hem niet kenden!, Amsterdam: “Stadhuis (Amsterdam). Bureau voor Pers, Propaganda en Vreemdelingenverkeer”, ca. 1945 , p. 3-4.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 14 March 1944, in: The Collected Works, transl. from the Dutch by Susan Massotty, London [etc.]: Bloomsbury Continuum, 2019.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 22 December 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Rantsoeneering van levensmiddelen in de bezettingsjaren, p. 2-5.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 5 November 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Het Vaderland, 4 september 1942, ochteneditie.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 10 and 14 March 1944, 15 april 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Rantsoeneering van levensmiddelen in de bezettingsjaren, p. 8.

- a, b Amsterdams Distributiedienst zooals de Duitschers hem niet kenden!, p.. 5-6.

- ^ Gerard Trienekens, Voedsel en honger in oorlogstijd 1940-1945. Misleiding, mythe en werkelijkheid, Utrecht: Kosmos-Z&K, 1995, p. 142.

- ^ "Koffie van de bon", Laarder Courant de Bel, 15 januari 1952.