Benjamin Holländer (1859)

Benjamin Holländer was a first cousin once removed of Edith Frank-Holländer.

Benjamin Holländer was a son of Moises Holländer (1832-1911)[1] and Hubertina (Tina) Hartog (1835-1900).[2] Moises was a great-uncle of Edith Frank Holländer, namely a half-brother of (Carl) Benjamin Holländer, Edith's grandfather.[3]

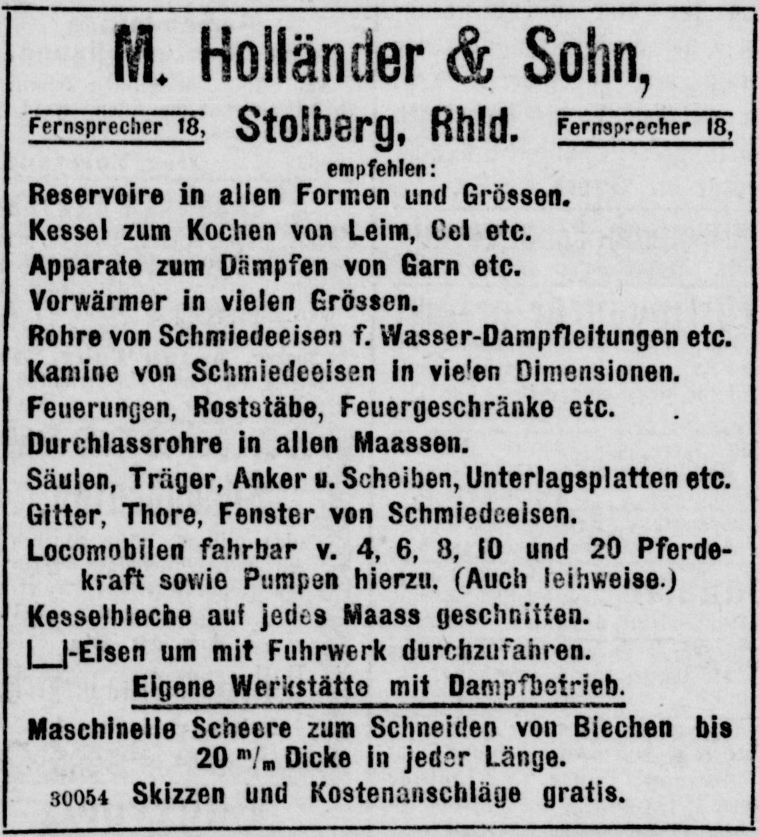

Benjamin was born in a family of ten children and had four brothers and five sisters. Their father Moises was the owner of a company, M. Holländer, which traded in scrap paper, rags and scrap metal and metal. The first mention of this company dates back to 1869.[4] In 1888, the company moved from Röhe to Eschweiler, and was renamed M. Holländer & Sohn in 1890.[5] This company manufactured and traded in locomobiles, steam boilers, transmissions and skid plates, among other things. After becoming co-owner in 1890, full ownership of the firm passed to son Benjamin in 1891.

That business was not always good is evidenced by a forced sale of some of the company's assets in April 1895[6] and bankruptcy proceedings against Benjamin Holländer a month later.[7] Bankruptcy was declared in September of that year.[8] The firm of M. Holländer & Sohn was finally deregistered from the trade register in November 1921, and Benjamin Holländer continued with a new company with the business name B. Holländer & Söhne.[9]

Benjamin Holländer was married to Wilhelmina Lichtenstein (1860-1924). They had four children: Sophia (1892), Leo (1893), Friedrich “Fritz” (1895) and Frieda (1898). Both sons served in the German army during World War I: one of them, Leo, was a fighter pilot and was awarded the “Iron Cross Second Class” (EK-II).[10] Fritz and Leo also participated in their father's business, which was located at the address Münsterbachstraße 1 (formerly Velauerstraße) in Atsch, a town in the German municipality of Stolberg, state of North Rhine-Westphalia. According to a 1928 advertisement, this company traded and rented railroad equipment: rails, dump cars, turnouts, turntables, and other hardware.[11]

Because of business relations with Dutch companies, the Holländers regularly traveled to Limburg, where they also visited a family branch that had emigrated to the Netherlands. Possibly this included Erich Holländer, a grandson of Moises Holländer and (great) nephew of his (grand) children.[12] But in February 1937 the Industrie- und Handelskammer and the bureau of the Staatspolizei in Aachen determined that only son Leo, who maintained most of the foreign contacts, could still receive a travel pass. After the 16 November 1937 decree of the Ministry of the Interior that stipulated that Jews could no longer obtain passports except in the interest of the Reich or for emigration, foreign travel by German Jews became virtually impossible. Yet Leo Holländer still enjoyed some freedom of movement because of his past as a fighter pilot. It was even rumored that he had met Hermann Göring several times and therefore enjoyed a certain untouchability.[10]

As part of the arization of Jewish businesses, the Industrie- und Handelskammer also had its eye on B. Holländer & Söhne. Benjamin Holländer, however, was unwilling to sell his company “voluntarily". But with the November pogrom of 1938, everything changed. Leo and Fritz were arrested on 10 November 1938, but unlike Fritz, Leo was released just one day later after protests from father Benjamin, who declared that he had to lay off all the employees of his company for lack of competent leadership. Friedrich was interned as a Schützhaftling in Buchenwald concentration camp, where he was held prisoner for four weeks. He came out of there in physically poor condition, tried to emigrate to Mexico, but was unsuccessful.[13]

After the Verordnung über den Einsatz des jüdischen Vermögens of 3 December 1938, Leo and Fritz's driver's licenses were declared invalid and private ownership of passenger cars for Jews was prohibited. It was further stipulated that Jewish businesses, land holdings and assets had to be sold at short notice. Because of these coercive measures, the Holländers could not do otherwise. In April 1939, the company was polarized and bought by an entrepreneur from Aachen, a dealer in iron and other metals.[14] Benjamin, now eighty years old, emigrated to Maastricht with his daughter Frieda and housekeeper. Benjamin had to deposit his entire fortune in a Sperrkonto (escrow account). When the 11. Verordnung zum Reichsbürgergesetz, a decree that stipulated that German Jews residing abroad lost their citizenship, of 25 November 1941 took effect, his assets fell to the German Reich.[15]

After the German invasion of the Netherlands, the Nazis deported Benjamin Holländer to Auschwitz via the camps Vught and Westerbork,[16] and his daughter Frieda to Sobibor.[17] Daughter Sophia was also a victim of the Holocaust. Her husband had fled to South America, but upon arrival in Paraguay he died of a heart attack.[18] Son Fritz was deported to Izbica, a transit ghetto in eastern Poland, on 22 March 1942.[19] His wife Helena was deported to Theresienstadt in 1942 and died there. [20] Leo Holländer and his wife emigrated with their children Walter, Wilhelmine (Wilma) and Doris on 27 July 1939 - one month before the outbreak of World War II - to Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe), escaping the persecution of Jews.[21]

Ten Stolpersteine (stumbling stones) now commemorate the Holländer family from Stolberg.[22]

Source personal data.[1]

Footnotes

- a, b Familienbuch Euregio: Benjamin Holländer.

- ^ Familienbuch Euregio: Tina Hartog. Hubertina (Tina) Hartog was a cousin of Albert Hartog, whose first and second spouse were sisters of Abraham Holländer, Edith's father. Not only was Abraham's broher0-in-law, he was also his stepnephew. Gudula Mencken, Albert's stepmother, was a sister of Sara Mencken, Abraham's mother.

- ^ Wilma Neumann writes that her grandfather was a brother Abraham Holländer, Edith's father, but this is incorrect. Wilma Neumann (née Holländer), Wilma's story: growing up in Nazi Germany and colonial Rhodesia, Watford: Print Forum, 2016, p. 19.

- ^ Echo der Gegenwart, 15 August 1869. Retrieved via Deutsche Zeitungsportal.

- ^ Echo der Gegenwart, 21 July 1888. Retrieved via Deutsche Zeitungsportal.

- ^ Zwangs-Versteigerung. Echo der Gegenwart, 17 April 1895. Retrieved via Deutsche Zeitungsportal.

- ^ Konkursverhafren. Aachener Anzeiger, 19 May 1895. Retrieved via Deutsche Zeitungsportal.

- ^ Konkursverhafren. Aachener Anzeiger, 8 September 1895. Retrieved via Deutsche Zeitungsportal.

- ^ Echo der Gegenwart, 9 November 1921. Retrieved via Deutsche Zeitungsportal.

- a, b Karen Lange-Rehberg e.a., “… nach Auschwitz verzogen”. Teil 2: Leben und Schicksal der verfolgten Juden aus Stolberg während der Nazizeit: eine Dokumentation der Gruppe Z, Aachen: Verlag R. Zillekens, 2021, p. 105.

- ^ Aachener Anzeiger, 15 September 1928. Retrieved via Deutsche Zeitungsportal.

- ^ Erich Holländer lived in Vaals since 1934 and moved to Heerlen in 1940. In 1937, he started IJzerwerk Hollander (Ironworks Holländer) in Spekholzerheide, Kerkrade.

- ^ Struikelsteentjes Maastricht: Holländer, Benjamin. Elsewhere it is suggested that he and his wife wanted to escape to Belgium, but that his sister Frieda talked him out of it. Manfred Bierganz, Die Leidensgeschichte der Juden in Stolberg während der NS-Zeit, Stolberg: Stolberg Burg-Verlag, 1989, p. 37-42.

- ^ Lange-Rehberg, “… nach Auschwitz verzogen”, p. 105-106

- ^ Lange-Rehberg, “… nach Auschwitz verzogen”, p. 106.

- ^ Joods Monument, Benjamin Holländer; Struikelsteentjes Maastricht: Holländer, Benjamin.

- ^ Joods Monument, Frieda Holländer; Struikelsteentjes Maastricht: Holländer, Frieda.

- ^ Neumann, Wilma's story, p. 30-31.

- ^ Struikelsteentjes Maastricht: Holländer, Benjamin; Bundesarchiv - Gedenkbuch: Opfer der Verfolgung der Juden unter der nationalsozialistischen Gewaltherrschaft in Deutschland 1933 – 1945: Holländer, Friedrich Fritz.

- ^ Bundesarchiv - Gedenkbuch: Holländer, Helene Helena.

- ^ They boarded passenger liner MV Bloemfontein of the Holland-Africa Line. They are listed on the passenger manifest: Anne Frank Stichting, Anne Frank Collectie, reg. code A_FamilieledenFrank_I_016: Passagierslijst van passagiersschip MV Bloemfontein.

- ^ Dirk Muller, Gedenken an die Stolberger Familie Holländer, Aachener Zeitung, 7 juni 2023; Wikipedia: Liste der Stolpersteine in Stolberg (Würselener Straße 39 en Münsterbachstraße 3).

Digital files (1)

Advertentie van M. Holländer & Sohn in de Aachener Anzeiger, 14 januari 1891

Copyright: Publiek domein

Photographer: De collectie kan worden ingezet voor het publiek.