Contact with the outside world

Once in hiding in the Secret Annex, many lines of communication with the former life of the people there were closed. Still, there was quite a lot of interaction with the outside world. Through the helpers, news from outside, reports about the old neighbourhood, newspapers and other reading material came in. There was also the radio, which was used to listen to the BBC and Radio Oranje.

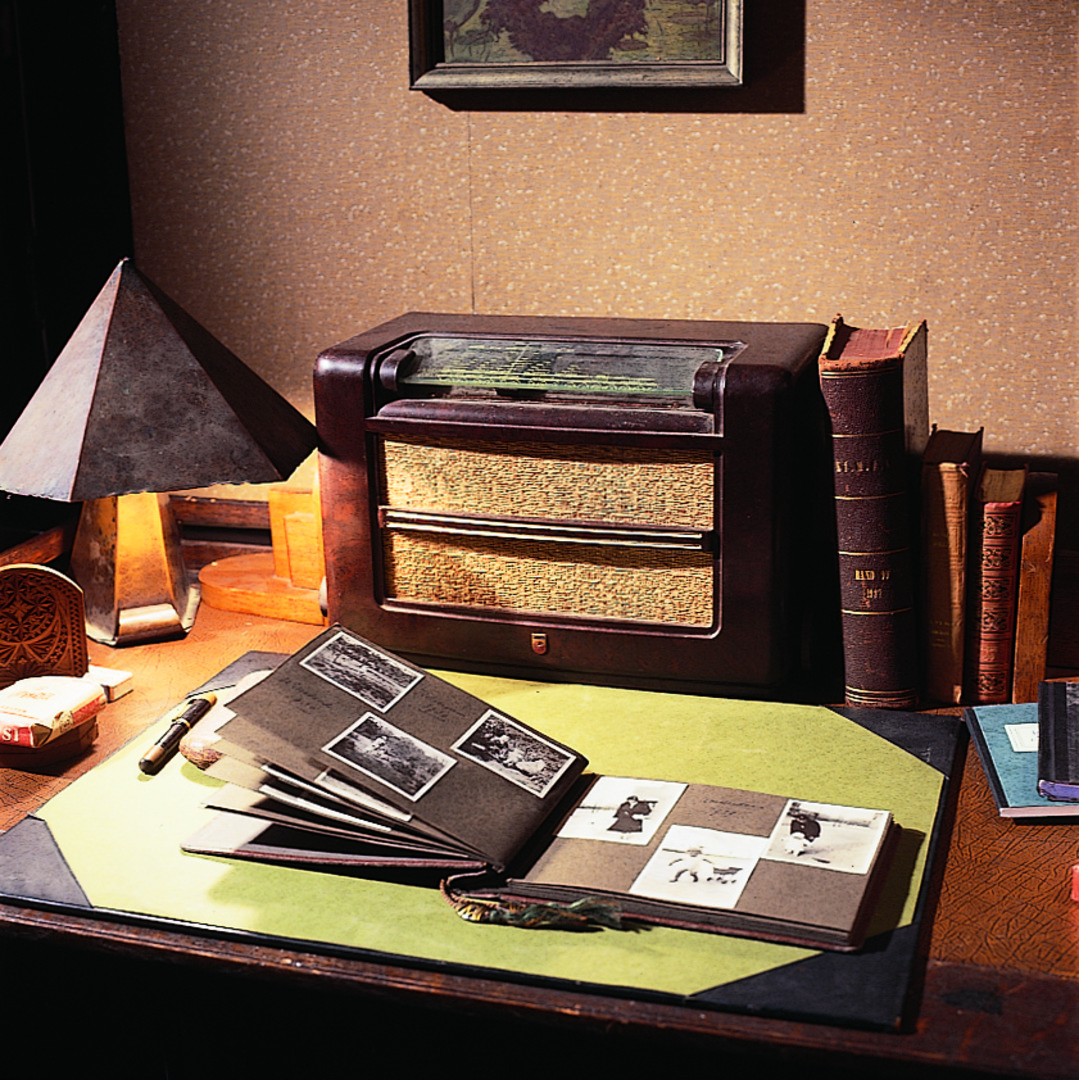

Radio en fotoalbum

Fotograaf: Allard Bovenberg. Collectie: Anne Frank Stichting. Copyright: AFS rechthebbende

Once in hiding in the Secret Annex, many lines of communication with people's former lives were cut off. They were very dependent on people outside, and supplies of all kinds of necessities of life went through the helpers. News from outside, reports about the old neighbourhood, newspapers and the like also came in through them. There was also the radio. Messages from the BBC and Radio Oranje were very important for the morale of the people in hiding. One very important broadcast, though, in retrospect, was Minister Gerrit Bolkestein's speech on 28 March 1944. Anne had been keeping a diary for some time by then. That night, however, she heard Bolkestein say:

'It [= the Dutch government in London] envisages the establishment of a national centre, where all the historical material concerning these years will be brought together, edited and published [...] If posterity is to fully realise what we as a people have endured and overcome in these years, we need precisely the simple pieces: a diary, letters from a worker in Germany, [...] ministers' sermons.'[1]

It was this speech that gave her the idea of writing 'a novel of the Secret Annex'.[2] This is what she began on 20 May 1944.[3] Her book, as we know, was later published in edited form and became world-famous. So this could be called a very essential contact with the outside world.

Reports about daily life

After the Franks moved into the Secret Annex, the only people they had direct contact with were the helpers, supplemented by Mrs Kleiman[4] and Bep Voskuijl's father. They provided direct information because they were aware of all kinds of news and had access to the mainstream and underground press. For example, Johannes Kleiman told Anne that the fire brigade had deliberately increased the damage when extinguishing the fire at the Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages with a lot of extinguishing water.[5]

Victor Kugler brought newspapers and magazines, such as Haagsche Post, Das Reich and Cinema & Theater.[6] Anne was interested in film and music, and noted in her diary that Bep Voskuijl went to performances by Thelma van Breemen and Evelyn Künneke.[7] She also mentioned concerts by Handel and Mozart that the radio broadcast.[8]

Anne often based her reflections on the state of affairs in the Netherlands and Amsterdam in 1944 on newspaper reports. She read and wrote about burglaries, missing persons, juvenile crime and vandalism.[9] Many such reports appeared in various newspapers. In the diary, Anne referred to reports and accompanying poems by Clinge Doorenbos from De Telegraaf, such as the case of the cat beaten to death in Hilversum.[10] The Normandy map also came from De Telegraaf.[11] Furthermore, 'Gies, Prinsengr. 263' placed a 'Speurder' classified advertisement in the newspaper looking to purchase a camera.[12] The advert also appeared in the Haagsche Post on 6 February. Although there are no explicit mentions of it, it appears that De Telegraaf was also read in the Secret Annex.

Reports on the progress of the war

Besides the helpers and the newspapers they brought, the radio was an important source of information. Anne describes the radio as a 'courage-keeping source'.[13] In September 1942, she writes about listening to German radio.[14] After Kugler was forced to hand in the large radio from the private office,[15] a 'baby radio' from Kleiman arrived in the Secret Annex.[16] Hermann van Pels heard about the fall of Mussolini around this time, possibly through this little radio.[17]

As time progressed, the people in the Secret Annex closely followed the battle on the Eastern Front. After D-Day, optimism rose,[18] and, using the Normandy map, they kept track of Allied progress. Several notes reveal that they also had access to information from underground sources. This explains how Anne was able to relate that there was supposedly a football match between military police and people in hiding, and that the Hilversum distribution service held consultation hours for people in hiding.[19] The first report is from Trouw,[20] the source of the second is unknown. Although people had been arrested at that service in late 1943, nothing is known about such consulting hours. In May 1944, she writes about plans for concentration camps in New Guinea.[21] The plan to intern NSB members on New Guinea was put forward in Het Parool just under a year earlier.[22] It is not clear whether the people in the Secret Annex had heard about this from a magazine, from the radio or heard it from the helpers.

Messages about family, friends and acquaintances

For the first few months, it was mainly Miep who brought reports about their former living surroundings. She recounted the scenes that accompanied the round-ups. Miep Gies brought reports of a search of her foster parents' home and how people were picked up from her neighbourhood.[23] When Anne writes about the fate of the Goslars and other acquaintances from Amsterdam-Zuid,[24] it is usually on the basis of this intelligence. Bep, who, although living with her aunt on Da Costakade during that period,[25] still came home a lot, was able to inform them that Anne's classmate Betty Bloemendal from Reinier Claeszenstraat had also been deported to Poland.[26] When Fritz Pfeffer came in November 1942, he knew the current state of affairs regarding the round-up of Jews in Amsterdam-Zuid.[27]

Kleiman had business correspondence with Erich Elias in Basel during the hiding period. He seemed to convey in veiled terms that everything was going reasonably well and inquired about the family there.[28] Thus, information seeped through about the state of affairs there, for example about Buddy's 'Künstler-neigungen'.[29] Alice Frank wrote in a postcard to Kleiman on 20 May 1945 that the last message she had received from him was dated 2 June 1944.[30] Kleiman also went once more to Werner Goldschmidt and to Albert Lewkowitz, to get hold of items left behind from the house on Merwedeplein.[31] Through Miep Gies, Pfeffer maintained a correspondence with Charlotte Kaletta. Edith Frank and Auguste van Pels were very much against this for security reasons.[32]

Again, it must have been through the helpers that the people in hiding heard that representatives Martin Brouwer and Hendrik Daatzelaar had been arrested for voucher trading. This was bad news in more ways than one: the loss of that source created shortages in the Secret Annex.[33] A short time later, Miep brought word that Mrs Stoppelman's son, his wife and sister-in-law had been arrested.[34]

The outside world intrudes

As Prinsengracht 263 continued to function as business premises, there was a lot of movement in the building. Suppliers, representatives and customers visited. The cleaning lady, Arthur Lewinsohn, the plumber, the carpenter and the accountant were also disruptive and frightening factors for the people in hiding.[35] Anne expressed her great fear of Willem van Maaren and the other warehousemen more than once.[36]

There were outsiders who could unwittingly notice something, but there was also representative Johan Broks who was curious about where Otto Frank had gone. In collusion with Kleiman, he was led astray with a complicated ruse, carried out via an unwitting Opekta customer in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen. The suggestion had to have been that the Franks had left for Switzerland via Belgium.[37]

A very undesirable form of confrontation with the outside world was experienced by the people in the Secret Annex when the premises became a target for thieves and burglars. Anne mentions four cases of break-ins and attempted break-ins during the period in hiding.[38] As far as is known, only the burglary of 9 April 1944 came to the attention of the police, because night watchman Martinus Slegers discovered the broken door.[39] An alerted policeman then inspected the premises.[40]

The immediate vicinity

Anne looked out past the curtains in the front office and saw passers-by there.[41] From the attic, she and Peter looked outside and they saw birds and the chestnut tree.[42] Once Anne also saw a small black kitten in the garden.[43]

Sounds from surrounding premises regularly penetrated the Secret Annex. In March 1944, there was a knock on the wall somewhere during dinner, causing alarm.[44] At weekends, they kept in mind the possibility that the nearby 'head of Keg' Jacob Boon could happen to drop by.[45] They seemed to perceive the Elhoek furniture factory on the other side as less threatening, although the staff there would take their breaks in the gutter near the Secret Annex when the weather was nice. One of them later stated that they did notice habitation, but without thinking of people in hiding.[46] More people from the block claimed to have noticed the presence of people in the Secret Annex, but these are all statements from the time when this history of the hiding was already very well known.[47]

Although there is an image of the Secret Annex as a kind of 'black box', completely detached from the outside world, it turns out that there was quite a lot of interaction with the outside world. To a large extent, admittedly, this was from the outside in. In this, the helpers were essential, as when Broks was led astray via a client in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen. Through the helpers, the lines of communication also ran to Overijssel, where the main focus of Brouwers' voucher business was located. Yet the most important line to the outside world was the one to Switzerland, which Kleiman maintained by postcard.

Footnotes

- ^ NIOD Instituut voor Oorlogs-, Holocaust- en Genocidestudies, Amsterdam, archief 206a, Europese dagboeken en egodocumenten: Transcriptie toespraak Uitzending Radio Oranje 28 maart 1944.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 29 March 1944, in: The Collected Works; transl. from the Dutch by Susan Massotty, London [etc.]: Bloomsbury Continuum, 2019.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 20 May 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 26 September 1942 en 31 mei 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 27 April 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 18 April 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 15 March 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 11 and 17 April 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 29 March 1944, in: The Collected Works

- ^ Artikel en gedicht, De Telegraaf, 27 april en mei 1944; Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 5 May 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Voorpagina, De Telegraaf, 8 juni 1944.

- ^ Onder “Diversen”, De Telegraaf, 2 februari 1943.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 15 June 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 21 September 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 3 August 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 15 June 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 26 July 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 6, 9, 13, 23 and 27 June 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 28 January 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Trouw, eerste jaargang, nummer 13 (midden november 1943).

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 11 May 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ “De komende afrekening”, Het Parool, 25 juni 1943.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 30 September 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 3 October and 2 November 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Stadsarchief Amsterdam (SAA), Dienst Bevolkingsregister, Archiefkaarten (toegangsnummer 30238): Archiefkaart E. Voskuijl.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 21 September 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 19 November 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Familiearchief AnneFrank-Fonds (AFF), Bazel, Erich Elias, AFF_ErE_odoc_04: ‘Plikarte’, 16 april, 12 mei, 8 september, 7 oktober en 10 december 1943, 4 mei 1944.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 30 June 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank Stichting (AFS), Anne Frank Collectie, Otto Frank Archief, reg. code OFA_072: Alice Frank aan Johannes Kleiman, 20 mei 1945.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 22 August 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 17 April 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 14 and 23 March 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 15 and 17 April 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 28 and 30 September, 1, 5, 15 and 20 October, 17 November 1942, 13 May 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 15, 18, 21 and 25 April 1944; Version B, 5 August and 16 September 1943; Tales and Events from the Secret Annex, "Lunch Break", 5 August 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 26 September 1942; Diary Version B, 25 September 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 1 March and 9 April 1944; Diary Version B, 16 July 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 9 April 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ SAA, Gemeentepolitie Amsterdam, inv. nr. 2036: Politierapport Warmoesstraat, 9 april 1944, mut. 23.25.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 2 November 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 23 February 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 30 September 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 10 March 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 25 April 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ AFS, Getuigenarchief, Van Pels: Mededeling van H. Pels, mei 1995.

- ^ AFS, Getuigenarchief, Broerse; Gesprek Dineke Stam met Sinie Broerse, 20 juni 1996; Dineke Stam, “‘Ik was de inbreker’ Hans Wijnberg: ‘Ik ontdekte dat daar onderduikers zaten’”, in: Anne Frank Magazine 1999, p. 32-35.