Reading in the Secret Annex

The people in the Secret Annex did a lot of learning and reading.

Boeken

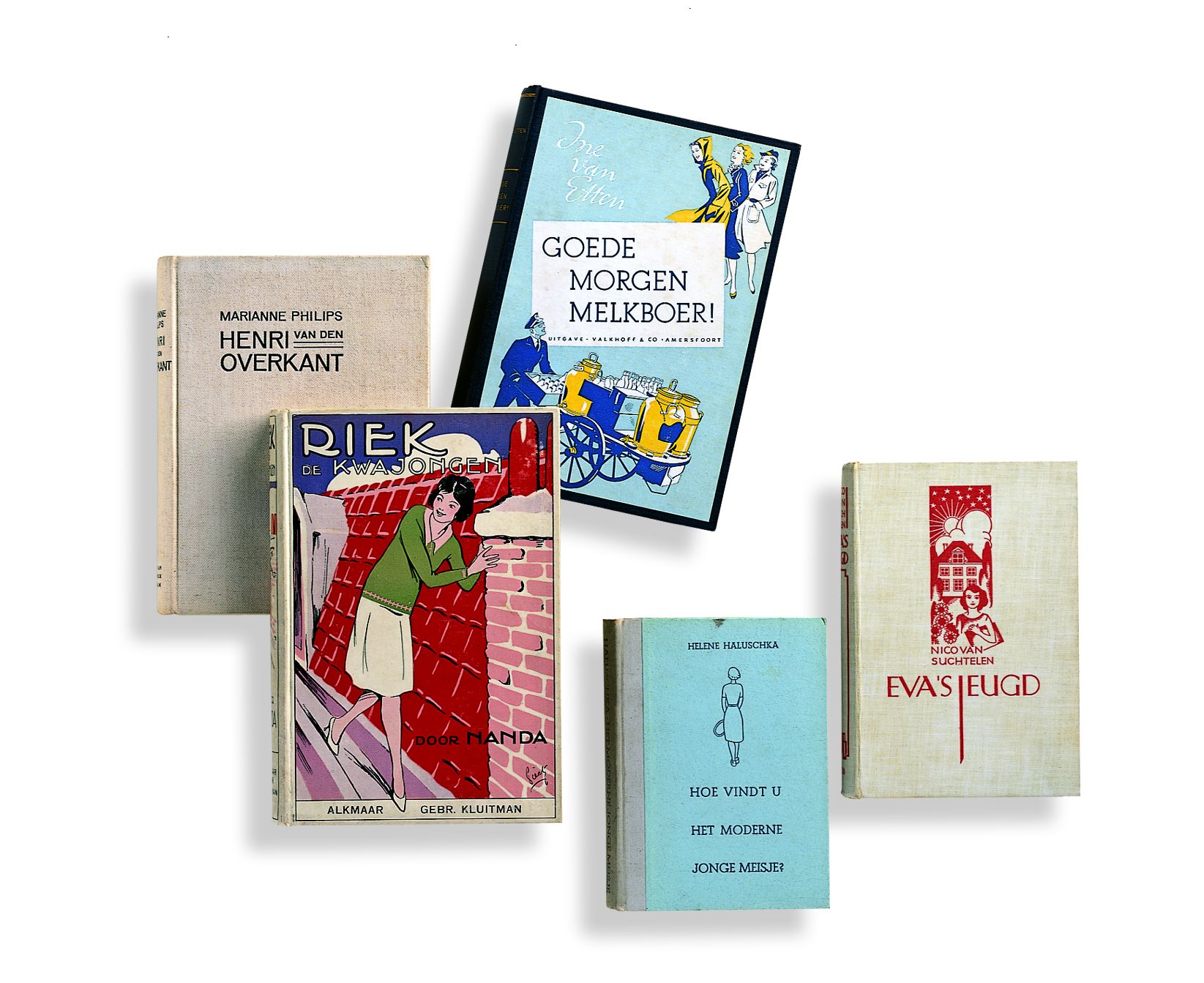

Fotograaf: Allard Bovenberg. Collectie: Anne Frank Stichting. Copyright: AFS rechthebbende

One of the pastimes on which the people in the Secret Annex spent their time was reading. There was initially a clear distinction between the adults and the children; several books were considered unsuitable for the young. Attitudes changed and the children grew up, as a result of which this naturally became less of a problem. Furthermore, the selection of books for children was closely linked to the aim of preventing the children falling behind at school. Specific issues around the learning theme were addressed in more detail with this. The reading material consisted of books brought to the Secret Annex by the people in hiding and books provided by the helpers. Johannes Kleiman brought books belonging to him and his daughter.[1] Jan Gies regularly took books from the C.O.M.O. reading library of his friend and former colleague Jacob Licht.[2]

The first entries in the diary about books are from 14 June 1942 and therefore predate the hiding period. Anne writes about the books she received for her birthday. These included the two volumes of Nederlandsche Sagen en Legenden ('Dutch Sagas and Legends') by Josef Cohen. She gave volume 1 to a neighbour girl before she went into hiding, who gave it to the Anne Frank House seventy years later. This reunited the two volumes for the first time since 1942. Over time, Anne's reading gradually became more mature.[3]

Parental and other supervision

In September '42, Kleiman brought a book that sparked a minor controversy in the Secret Annex. It was a book 'from the previous war ' and because, according to Anne, it was 'very freely written' , Peter and Margot were not allowed to read the trilogy in question.[4] According to Anne, the book's theme was a 'women's topic '.[5] According to the characteristics that Anne noted - a book from the time of the First World War, with a women's subject, 'freely written ' - and moreover a trilogy published in one volume before September 1942, there is only one book that this could have been, namely Gij Vrouwen..!, Vrouwen in nood and Vrouwenroeping by Australian-British writer Helen Zenna Smith,[6] which had been published by De Arbeiderspers in 1938. These books - Dutch translations of Not so quiet: stepdaughters of war (1930), Women of the aftermath (1932) and Shadow women (1932) - told the story of some English girls of good character who were ambulance drivers behind the front carrying off wounded soldiers. The author depicted the accompanying coarsening rather explicitly.

At the same time, Edith was reading Heeren, knechten en vrouwen (The House of Tavelinck) by Jo van Ammers-Küller. Anne wanted to read this too, but she was not allowed to.[7] When Anne read Marianne Philips' Henri van den overkant (Henri from the Other Side), she received negative comments from Pfeffer and Mrs Van Pels.[8] In March '44, Anne wrote in her diary that she was annoyed that her reading was supervised, while adding that she was actually allowed to read almost anything.[9] She writes that she is happy to be allowed to read some more 'mature books', and gives this statement the date of late October '42. But as this is in the B version, it was therefore actually written much later.[10]

Cissy van Marxveldt and other children's books

Anne enthusiastically read the various volumes of Joop ter Heul, and even read Een zomerzotheid (A Summer Folly) four times.[11] The books Kleiman brought along included Van Marxveldt's De louteringskuur (The Purification Cure).[12] She based her own Jopopinoloukico club on the characters from the Joop ter Heul series. In her first diary (the A-version), she addressed her letters to Pop, Conny, Marianne, Kitty and others. Over time, Kitty remained.

Kleiman brought Het boek voor de jeugd (The Book for Young People) for Anne. He also lent other children's books, such as Else’s baantjes (Else's jobs) and Riek, de kwajongen (Riek, the tomboy), to the people in the Secret Annex. These belonged to his daughter, and he took them on the pretext of lending them to Bep's sisters.[13] Anne also wanted to read Kees de jongen (Young Kees) by Theo Thijssen, but it is unclear whether this happened.[14]

History, religion, philosophy, art, culture and politics

Both Otto Frank and Anne were interested in mythological and historical subjects. Otto had been a grammar school student and in 1908 he attended a summer semester of art history at Heidelberg University, where he was taught in those subjects, among others.[15] Edith also attended grammar school in Aachen. She possessed several philosophically and religiously oriented books, some of which also went with her to the Secret Annex. Some of these belong to the museum collection of the Anne Frank House.

Anne did not like the way her mother insisted on reading a prayer book, but for form she read some prayers 'in German'.[16] Anne preferred reading about films and movie stars. Victor Kugler therefore regularly brought the magazine Cinema & Theater for her.[17] She referred to what she read in it in her diary and in the little story 'The Pool of Decay'.[18]

In May 1944, Palestina op de tweesprong (Palestine at the Crossroads) by Hungarian journalist László Faragó was present in the Secret Annex, and Anne started reading it too.[19] Around the same time, she wrote that her sister Margot wanted to become a maternity nurse in Palestine.[20] It is plausible that this idea arose from reading this book, which discusses childcare in Palestine by trained nurses several times.[21]

For her last birthday, 12 June 1944, Kugler gave Anne a biography of Maria Theresia, by Zdenko von Kraft. Gifts also included Anton Springer's five-volume art history series, which was already present in the Secret Annex.[22]

Literature

Of the inhabitants of the Secret Annex, Edith Frank was the one with the most literary baggage, according to Anne.[23] Others also read well-known literature. Anne wrote several times about her father reading Dickens, without mentioning any titles.[24] He used it to learn English, so he read it in the original language. [25] In the museum collection of the Anne Frank House, there is a copy of Sketches by Boz that came from Otto Frank.[26] Pfeffer read Henri van den overkant (Henri from the other side) by Marianne Philips, and praised it; Anne was less enthusiastic.[27] In April 1944, she transcribed an unknown play by Carry van Bruggen.[28]

Earlier that year, the inhabitants of the Secret Annex read Ochtend zonder wolken (Morning without clouds), the first part of the trilogy De geschiedenis van Robin Stuart (The history of Robin Stuart) by Australian writer Eric Lowe.[29] The Dutch translation of this trilogy, originally published as a one-volume novel, entitled Salute to freedom, was by renowned Dutch author Simon Vestdijk. Anne included a passage from the second part, De terugkeer van de held (Return of a hero), in her Favourite Quotes Notebook. Given this book of quotations, she also read works by Multatuli, Justus van Maurik, Shakespeare and Jacob van Maerlant.[30] With her father, she continued to read works by the German poet and playwright Theodor Körner, and he wanted her to read works by German playwright Friedrich Hebbel as well.[31]

Trilogies were popular in the Secret Annex: besides Helen Zenna Smith's trilogy mentioned above and the books about Robin Stuart, Anne mentions the Bjørndal-trilogy by Norwegian writer Trygve Gulbranssen and Hongaarsche rhapsodie (Hungarian melody), the trilogy about the life of composer and pianist Franz Liszt by Hungarian writer Zsolt Harsányi. From this same author Anne read romanticized biographies of painter Peter Paul Rubens and physicist Galileo Galilei. The Favourite Quotes Notebook shows that she also read at least one part of Sigrid Undset's Kristin Lavransdatter-trilogy. She quotes a passage from the part entitled The wife, in any event, which indicates that she read it.[30]

Newspapers and magazines

Newspapers were read in the Secret Annex. Anne writes in late 1942 about a newspaper report following the execution of hostages.[32] In February 1944, she reports that all the newspapers were speculating about an imminent invasion.[33] Exactly which newspapers were available is not known, but Anne sometimes quoted Clinge Doorenbos writing in De Telegraaf .[34] Several other diary entries also indicate the presence of this newspaper. Anne also notes on 26 October 1942 that Kugler brought them twelve issues of Panorama: 'now we have something to read again'.[35] At least in early 1944, Kugler still brought Cinema & Theater, the Haagsche Post and occasionally Das Reich every week.[36] Some notes show that she actually read Cinema & Theater and the Haagsche Post .[18]

Several notes also reveal that the people in hiding read clandestine magazines, or at least took note of them. Anne copied an allegation from a 'reliable source' that there had been a football match between people in hiding and military police somewhere in the Netherlands.[37] Anne also made references to Vrij Nederland.

As far as can be seen, among the adults, Mr and Mrs Van Pels were the least engaged in reading. Mrs Van Pels did read Henri van den overkant, as she discussed this with Pfeffer and Anne. Most of the information on the reading behaviour of Mr and Mrs Van Pels comes from Anne's diary, so there is a chance that the picture is distorted.

Footnotes

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 10 October 1942, in: The Collected Works, transl. from the Dutch by Susan Massotty, London [etc.]: Bloomsbury Continuum, 2019.

- ^ Miep Gies & Allison Leslie Gold, Herinneringen aan Anne Frank. Het verhaal van Miep Gies, de steun en toeverlaat van de familie Frank in het Achterhuis, Amsterdam: Bert Bakker, 1987, p. 108.

- ^ See: Ton J. Broos, 'Anne Frank's literary connections', in: Josef Deleu (chief ed.), The Low Countries, arts and society in Flanders and the Netherlands, Rekkem: Stichting Ons Erfdeel, 2000. - p. 177-189; Sylvia Patterson Iskander, 'Anne Frank’s reading', in: Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, 13 (1988) 3 (Fall), p. 137-141.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 21 September 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 2 September 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Pseudoniem van Evadne Price, waarschijnlijk geboren als Eva Grace Price, een Australisch-Britse schrijfster, actrice, astroloog en media-persoonlijkheid. Zie verder Wikipedia: Evadne Price (geraadpleegd 22 oktober 2022).

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 22 September 1942, in: The Collected Works..

- ^ Anne Frank, Tales and events from the Secret Annexe, “Anne in theory”, 2 August 1943; Diary Version B, 29 July 1943, in: The Collected Works..

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 17 March 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 29 October 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 28 September 1942; Diary Version B, 21 September 1942, in: The Collected Works..

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 18 October 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 10 October 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 22 September 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Universitätsarchiv Heidelberg, StudA 1900-09/10 Frank, Otto: 'Studien- und Sittenzeugnis Dem Herrn Otto Frank'.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 29 October 1942, in: The Collected Works. Edith Frank had in her posssesion a Hebrew-German prayerbook. Anne Frank Stichting (AFS), Anne Frank Collectie (AFC), reg. code A_EFrank_VII_021: W. Heidenheim (Hrsg.), Gebete für das Wochenfest mit deutscher Uebersetzung, Roedelheim : Druck und Verlag von M. Lehrberger und Comp. 1893.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 22 January 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- a, b Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 19 April 1944; Tales and events from the Secret Annexe, “The den of iniquity”, 22 February 1944, in: The Collected Works..

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 11 May 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 8 May 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ AFS, AFC, reg. code B_Achterhuis_VII_033: László Faragó, Palestina op de tweesprong, Amsterdam: Nederlandsche Keurboekerij, 1937, p. 214, 237-238.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 13 June 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Tales and events from the Secret Annexe, “The Annexe eight at the dinnner table”, 5 August 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 4 March 1944; Diary Version B, 5 August 1943; Tales and events from the Secret Annexe, “Lunch break”, 5 August 1943, and “Wenn die Uhr half neune slagt....”, 6 August 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, undated (May 1944), in: The Collected Works.

- ^ AFS, AFC, reg. code A_OFrank_VII_006: Charles Dickens, Sketches by Boz. Illustrative of every-day live and every-day people, London: Chapman & Hall: Frowde, s.a.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version B, 29 July 1943, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 19-21 April 1944 (Secret Code), in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 12 January 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- a, b Anne Frank, The favourite quotes notebook, in: The Collected Works

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 18 October 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 8 October 1942, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 3 February 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 5 May and 9 June 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 26 October 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 18 April 1944, in: The Collected Works.

- ^ Anne Frank, Diary Version A, 28 January 1944, in: The Collected Works. The source of the report is Trouw, vol. 1., no. 13, November 1943.